How CSD merges the queue(3) and STL container designs

CSD lists aim to reimplement the original queue(3) lists as STL-compatible containers. It is not possible to do this without a few design conflicts, so CSD lists are different from both queue(3) lists and typical STL containers. This page summarizes those differences.

Differences between CSD lists and other STL containers

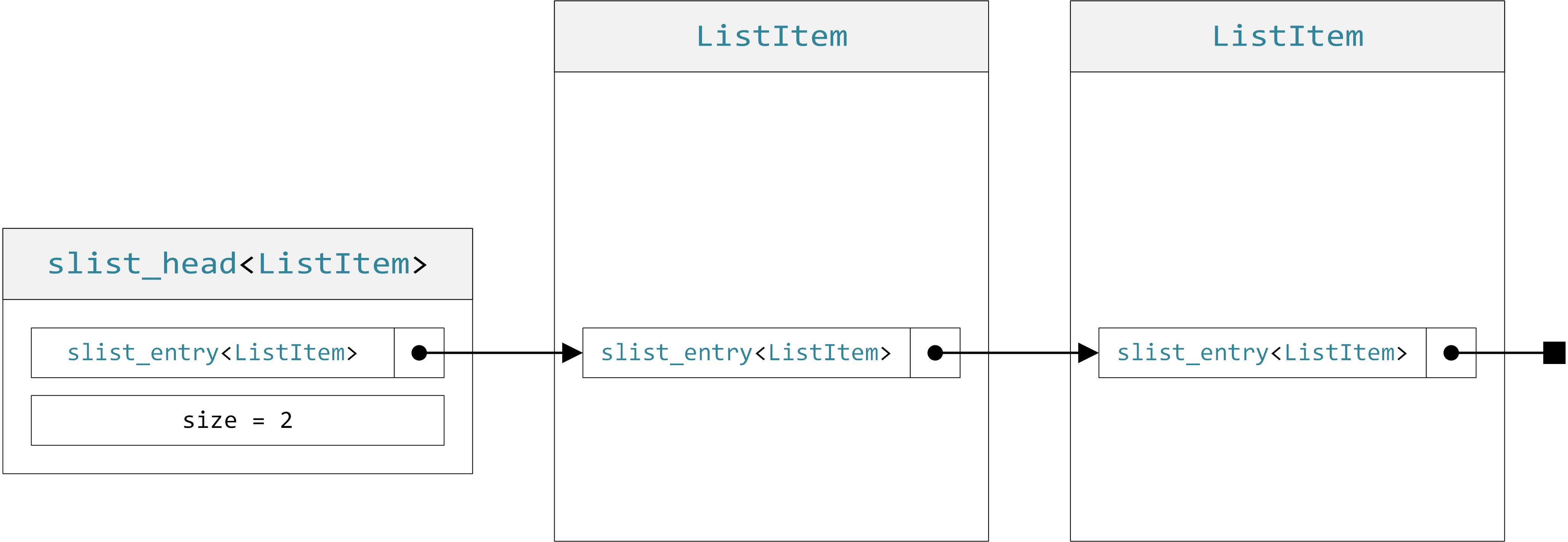

The primary difference between CSD lists and STL containers is explained briefly in the quick start guide, namely that CSD lists do not own their objects whereas STL containers do. A CSD “list object” is just a small “list head” structure, containing pointers to the intrusive links to the first (and sometimes last) element of the list items.

Lack of ownership gives rise to many small differences, including:

List items are neither copied nor moved into the list – they are just added to it (their intrusive link member variable is modified to splice the item into the list).

As a consequence of the above, list items are always inserted by pointer, i.e., for a list of type

T, theinsertfunction requires aT*value. This emphasizes that insert is not copying or moving the item, but just modifying it. To avoid breaking with the standard container patterns too much, all non-insertion member functions continue to useT&, e.g.,front()andback()continue to return the item, not a pointer to it. However, all insertion-oriented member functions, e.g.assign, accept pointers-to-items.As another consequence, CSD lists cannot be copied or copy-assigned. A copy would imply that two identical lists could be created, i.e., that a list item could live in multiple lists at the same time, using the same entry link. Looking at the diagram above, it should be clear that this is not possible. To live in multiple lists, multiple entry links are required.

The list destructor doesn’t actually destroy the items (because it does not own them); it only edits the head object to make the list empty.

There is no

emplacemethod; because the caller always creates and destroys the items and not the list itself, it does not make sense to construct an item “inside” the list.All other STL functions that do not “make sense” in the

queue(3)ownership model aren’t defined, for example,resize.

Methods in CSD lists that do not exist in the STL

iter and citer

Given a pointer to a list item, the caller may construct a list iterator pointing to that item in \(O(1)\) time using the iter (or citer for const) member function, for example:

ListItem L{.data=123;}

list_t myList;

myList.insert(&L);

// ...somewhere else in the code...

ListItem *p = /* obtain a pointer to `L` */

list_t::const_iterator i = myList.citer(p);

assert(i->data == 123);

Implicit converting constructors from pointers to iterators

Assume list_t is a tailq in the following code:

list_t myList;

ListItem L1;

myList.push_front(&L1);

myList.erase(&L1);

Although erase takes a const_iterator and not a pointer to a list item, the pointer is implicitly convertible to a list iterator (via a converting constructor in iterator), as long as the EntryEx template argument is stateless (i.e., both empty and trivially constructible). If EntryEx is not stateless, the iter and citer methods must be used instead.

Warning

Users should be careful with both this feature and with iter/citer: there is no cheap way within CSD itself to check that an item is actually a member of that list. The tailq_entry object does not record the identity of the list that the item is in; it only stores the instrusive list linkage to neighboring items. An item is “in” a list only because a traversal starting from the head would happen to visit it.

Because the links are stored directly inside the items, a pointer to an item is all that is needed to construct the iterator type (which simply traverses the links) whether or not the link members are actually valid and pointing inside the list in question.

for_each_safe

Because CSD lists implement the common STL patterns, this will work:

for (const ListItem &s : myList)

std::cout << "item #" << s.i << std::endl;

But this will not:

for (ListItem &s : myList)

delete std::addressof(s);

The problem is that, because the list links are intrusive, destroying an item also destroys the entry object needed for the iterator increment. The range-based for loop above is equivalent to:

auto i = std::begin(myList);

const auto end = std::end(myList);

while (i != end) {

delete std::addressof(*i);

++i; // ERROR: tries to read the entry object inside of the deleted *i

}

Slightly restructuring the loop would fix the problem:

auto i = std::begin(myList);

const auto end = std::end(myList);

while (i != end)

delete std::addressof(*i++);

This works because the list’s post-increment operator will advance the iterator (reading the neighbor link immediately), and return a copy of the old iterator for use in the expression. Although the object is no longer accessible at the end of the full expression, the iterator has already been incremented.

Each CSD list has a for_each_safe member function that is similar to the std::for_each algorithm in <algorithm>, except that it uses the post-increment pattern above, to safely visit the list when the visitor might modify the links. Because the list does not own the items (and therefore the destructor does not destroy them), list items are often destroyed by visiting the items with for_each_safe and destroying each one. The header <csg/core/intrusive.h> also defines a for_each_safe free function, as the need for it is common to all intrusive data structures. The name comes from the FOR_EACH_SAFE macro in the original queue(3) library.

find_predecessor and find_erase

Both slist and stailq adhere to the singly-linked list design from the C++ standard, <forward_list>. This means that the caller often needs the predecessor iterator to call a function, e.g., erase_after, insert_after, splice_after, etc.

So how do you, for example, erase an item if you only have the iterator to it, but not the predecessor? Both slist and stailq provide a member function called find_predecessor which returns an iterator to the prior item – the find part of the name emphasizes that it will perform a (linear time) search. Another new function, find_predecessor_if, accepts a unary predicate (as in the STL algorithm std::find_if) and returns a pair of the predecessor iterator for the first matching element and a boolean indicating if a matching element was found. The boolean is present because, in the case where no item was found, the iterator returned is the predecessor of end(), rather than end() itself. Since the returned iterator can never be end() – even in the case of an empty list it would be before_begin() – the boolean saves the caller from needing to check if std::next(i) == std::end(list) to see whether or not the item was actually present.

A convenience method, find_erase, combines find_predecessor and erase_after to erase an item given an iterator to it. This is a design difference between CSD and the original queue(3) library. In queue(3), the SLIST_REMOVE and STAILQ_REMOVE macros are implemented this way, so their performance is \(O(n)\) instead of the \(O(1)\) performance of LIST_REMOVE and TAILQ_REMOVE despite having the same name. In CSD we give the method a different name to emphasize that it has a different runtime cost. find_erase returns a pair, where the first element is the pointer to the erased item and the second element is the iterator to the next item, as normally returned by erase_after.

Differences between CSD lists and queue(3) lists

The biggest difference is that the CSD list data structure is just a deprecated alias for tailq – because they aren’t actually different data structures! In fact, list was only included so that users familiar with queue(3) would find it, notice the deprecation, and hopefully read this explanation rather than wondering why it didn’t exist at all.

In the queue(3) library, LIST is a doubly-linked list that does not maintain a link to the last element. This allows the list’s head object to be smaller than a tailq head by one pointer – a valuable savings if you design compact data structures that make optimal use of cache lines.

Unfortunately, this is incompatible with the STL design – not only does an STL-style list provide bidirectional iterators, but the expression --mylist.end() is valid and must yield the last element. Moreover, the last element is readily accessible via the T &back() accessor method, and (like all other containers that provide it) the push_back method should provide amortized \(O(1)\) insertion performance.

There is no way to do this with a list head that consists of only a single pointer. There were five options:

Implement

listas it is inqueue(3), and make its interface incompatible with the STL.Implement

listas a single pointer to a head data structure that is larger – some dynamic memory allocation would be needed to grab the external head storage.Implement

listthe exact same way astailqto satisfy the additional STL requirements. In this case, only one data structure needs a real implementation – the other can be a type alias.Do not implement

listat all.Implement

listas atailqtype alias and deprecate it, generating warnings whenever it is used.

Option (1) conflicts too much with design goals of CSD. Option (2) conflicts with the C/C++ culture of preferring lightweight abstractions – if you really want a single pointer to save space at the cost of an indirection, you can store a pointer to a tailq_head and implement this option yourself. Option (3) is misleading – list is available, but doesn’t provide the size advantage over tailq that it does in the queue(3) library. Option (4) leaves queue(3) fans wondering why list is missing. Option (5) – what is actually implemented – allows users to discover that there is a list, but that they shouldn’t use it.

Hopefully this causes them to read this documentation and discover that (1) list cannot keep its traditional head-size advantage over tailq in an STL-compatible world and therefore (2) the only reasonable STL-compatible implementation of a doubly-linked list must be the data structure that queue(3) calls a “tail queue.” Therefore, even though they have the same implementation, tailq is considered the “right” name for the data structure and the list name is deprecated.