Why Intrusive Lists?

Linked lists? Aren’t those maddeningly slow data structures?

You can find many blogs showing that std::list performance is terrible compared to more popular choices. Even worse, Bjarne himself says that the “default advice is to prefer to std::vector.” What hope is there for lists, let alone intrusive lists? Do they have any place in the modern programming world, aside from “white board” parlor tricks during your job interview at the local spaghetti-code factory?

If you’ve mentally written off lists, at least ponder the following:

If intrusive lists are so bad, why do they appear everywhere in operating system kernels, which are some of the best-engineered pieces of software in existence?

I’ve heard many people who don’t know the answer try to guess at it. “The code base is so old,” they say, “it probably predates the memory wall! If they rewrote it today, the whole thing would be vectors!”

No, it would not.

There are actually two different reasons. The first is stylistic rather than technical: intrusive data structures end up making large codebases “easier to understand.” Put simply, they help make your code “good” when used correctly.

The second reason is deeper than you might think – so deep that it goes right to the heart of the dysfunction in modern computer programming. Intrusive data structure design provides a clean way to place an object in multiple containers at once, allowing them to clearly model complex relationships. The “dysfunction” spoken about above is that most programmers do not know any good design patterns for how to model complex relationships, and thus fall into one of several classic anti-patterns which plauge many pieces of software. 1 The judicious use of intrusive data structures can prevent this.

To be more accurate, these are not really two different reasons but a “what?” and a “how?”. Clean modeling of complex relationships is what intrusive data structures do for you. How they end up being “cleaner” is a consequence of the code style they naturally foster.

What makes code “good”?

The art of programming is the art of organizing complexity, of mastering multitude and avoiding its bastard chaos as effectively as possible. – Edsger Dijkstra

How many spaces do you indent? Four seems to be a popular choice these days, but my own style was influenced by LLVM – the first well-written C++ program I stumbled across – which uses only two. Although I have to admit, there isn’t much of a difference between this:

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Wrong number of arguments!\n");

return 2;

}

return start(argv);

}

and this:

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Wrong number of arguments!\n");

return 2;

}

return start(argv);

}

but I suspect this will make you uncomfortable:

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Wrong number of arguments!\n");

return 2;

}

return start(argv);

}

and this definitely will:

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Wrong number of arguments!\n");

return 2;

}

return start(argv);

}

As all programmers know, indentation is critical to how we understand program structure, especially flow control. Most of us take it for granted that some attention to formatting is important, but there is a surprising lesson when we start to ask why.

Computers obviously do not need indentation – it gets compiled away. The purpose of those compilers is to translate a program between two languages that have vastly different properties. The source language is full of human-sensitive cues that make comprehension easy. For example, any graphic designer will tell you that people are very sensitive to alignment cues, so language designers exploit vertical alignment (“indentation”) to convey “grouping” concepts. These choices are entirely motivated by patterns in human cognition; it has nothing to do with computers.

Source languages have a downside of course: it is difficult to design a machine that directly executes their code. Thus a “target language” (e.g., a CPU ISA) is designed to be “friendly” to a computation machine. Such languages are so explicit and tedious that it’s a cakewalk to design a machine for them, but they can only be understood by a human at tremendous mental cost. The role of compilers is the automatic translation of the same program between two such languages.

Thus, quality source code is primarily about understanding how to make ideas clear and obvious to a human. This isn’t just an “important dimension” of code quality, it is literally the only reason why we use programming languages at all. Yet sadly, most programmers are bad at it – their own code makes sense to them (at least for the moment) so why waste time trying to be clear?

How do data structures affect code quality?

There is tremendous focus in computer science education on technical matters, while almost no attention is paid to how programmers can make code more comprehensible. This isn’t surprising – the knowledge for what a garden-variety human finds clear or obvious tends to live outside the computer science department. In most cases, a psychology professor could tell you far more about the subject than a computer scientist.

Thus you might hear someone say “this data structure is great because it has \(O(1)\) insertion performance!” but you’ll never hear “this data structure is great because helps our program make sense.” It’s so rare to hear something like that, that you might even wonder how data structure choice can affect comprehension. After all, Alexander Stepanov largely succeeded at designing completely generic interfaces for containers, so you might think any ugly implementation details can hide safely behind those interfaces.

Consider, for example, a C++ std::unordered_map vs. a std::vector. What is the salient difference between the two? If you said something about the “big O” of various operations, this is technically true, but misses the point.

One critical difference is pointer stability or, in C++ parlance, when pointers to contained elements are invalidated (std::unordered-map almost never invalidates a reference to a contained element). The complexity of large software systems is primarily about the complexity of relationships between its many parts. If you can safely capture a pointer or reference to an object because you know it won’t disappear, you can write code that looks like this:

struct Child {

Parent *p;

}

It is impossible to look at this code and not understand what p is – it’s the child instance’s parent!

But if you don’t have pointer stability then you can’t do this. You need to store a key or index and perform a lookup, and the code ends up looking a little more obscure:

struct Child {

std::size_t parentIdx;

std::vector<Parent> *parents;

Parent &getParent() const noexcept { return (*parents)[parentIdx]; }

};

Notice what has happened here. Yes, we are using a vector and we may be rewarded with better performance in other parts of the system (e.g., algorithms that visit all Child elements). But the program structure has also changed. Our data is organized in a different way. It doesn’t look the same, and it’s slighty harder to “see” what’s going on. Of course it doesn’t matter much: this example is small and more importantly, there is only one relationship (a simple parent/child relationship). But as the number of relationships grows, the “comprehension cost” of the latter approach will grow enormously.

The real power of the intrusive list is that it makes code look more like the first example. As we’ll demonstrate with a real example in the next section, the fact that the links are intrusive has a profound impact on how the code is organized and especially on how you read it. All of this makes almost no difference on a technical level. Yes the cache locality can be worse than std::vector. Outside of micro-benchmarks, the negative cache effects are usually unimportant.

An example: the FreeBSD process tree

UNIX processes have a very complex set of relationships among themselves. A process has:

An entry in the process table (the global list of all processes)

A parent process

An entry in a process group

A numeric pid, which can be used to look up the process via a hash table

A list of siblings in the process tree (processes having the same parent)

A list of child processes

A reaper process, the ancestor that will adopt the process if it becomes a zombie

A “reap-list” of associated zombies if the process is acting as a reaper for its sub-tree

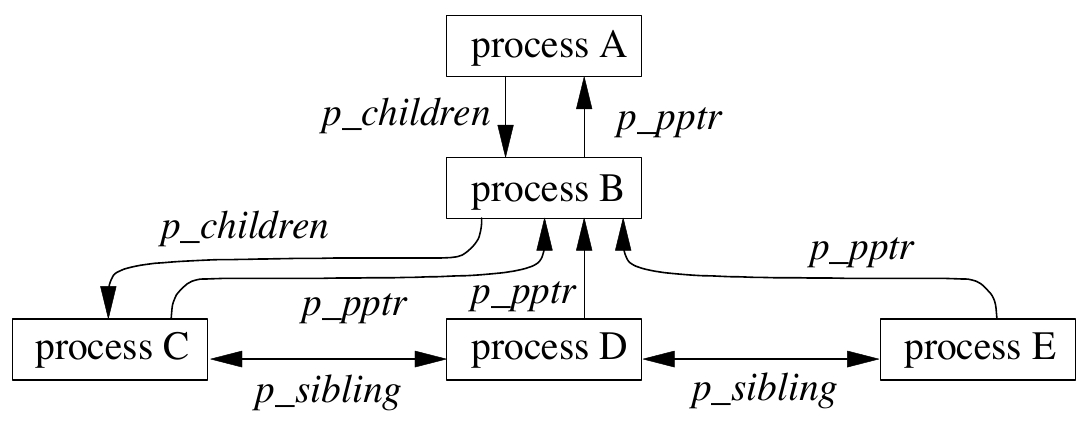

The figure below, taken from The Design and Implementation of the FreeBSD Operating System, depicts some of the relationship between processes:

An illustration of some of the relationships between processes, appearing in the “Process Management” chapter of The Design and Implementation of the FreeBSD Operating System.

If you think it would easy to forget what all these relationships are while looking at the FreeBSD source code…you would actually be wrong.

Look at the definition of the FreeBSD process structure (from <sys/proc.h>) and pay attention to the highlighted lines:

1/*

2 * Process structure.

3 */

4struct proc {

5 LIST_ENTRY(proc) p_list; /* (d) List of all processes. */

6 TAILQ_HEAD(, thread) p_threads; /* (c) all threads. */

7 struct mtx p_slock; /* process spin lock */

8 struct ucred *p_ucred; /* (c) Process owner's identity. */

9 struct filedesc *p_fd; /* (b) Open files. */

10 struct filedesc_to_leader *p_fdtol; /* (b) Tracking node */

11 struct pstats *p_stats; /* (b) Accounting/statistics (CPU). */

12 struct plimit *p_limit; /* (c) Resource limits. */

13 struct callout p_limco; /* (c) Limit callout handle */

14 struct sigacts *p_sigacts; /* (x) Signal actions, state (CPU). */

15

16 int p_flag; /* (c) P_* flags. */

17 int p_flag2; /* (c) P2_* flags. */

18 enum {

19 PRS_NEW = 0, /* In creation */

20 PRS_NORMAL, /* threads can be run. */

21 PRS_ZOMBIE

22 } p_state; /* (j/c) Process status. */

23 pid_t p_pid; /* (b) Process identifier. */

24 LIST_ENTRY(proc) p_hash; /* (d) Hash chain. */

25 LIST_ENTRY(proc) p_pglist; /* (g + e) List of processes in pgrp. */

26 struct proc *p_pptr; /* (c + e) Pointer to parent process. */

27 LIST_ENTRY(proc) p_sibling; /* (e) List of sibling processes. */

28 LIST_HEAD(, proc) p_children; /* (e) Pointer to list of children. */

29 struct proc *p_reaper; /* (e) My reaper. */

30 LIST_HEAD(, proc) p_reaplist; /* (e) List of my descendants

31 (if I am reaper). */

32 LIST_ENTRY(proc) p_reapsibling; /* (e) List of siblings - descendants of

33 the same reaper. */

34 struct mtx p_mtx; /* (n) Lock for this struct. */

35 struct mtx p_statmtx; /* Lock for the stats */

36 struct mtx p_itimmtx; /* Lock for the virt/prof timers */

37 struct mtx p_profmtx; /* Lock for the profiling */

38

39 /* ...many fields removed from CSD documentation... */

40

41 /*

42 * An orphan is the child that has beed re-parented to the

43 * debugger as a result of attaching to it. Need to keep

44 * track of them for parent to be able to collect the exit

45 * status of what used to be children.

46 */

47 LIST_ENTRY(proc) p_orphan; /* (e) List of orphan processes. */

48 LIST_HEAD(, proc) p_orphans; /* (e) Pointer to list of orphans. */

49 u_int p_ptevents; /* (c) ptrace() event mask. */

50 uint16_t p_elf_machine; /* (x) ELF machine type */

51 uint64_t p_elf_flags; /* (x) ELF flags */

52 sigqueue_t p_sigqueue; /* (c) Sigs not delivered to a td. */

53#define p_siglist p_sigqueue.sq_signals

54 int p_pdeathsig; /* (c) Signal from parent on exit. */

55};

The highlighted lines show either direct pointers (e.g., to the parent process and reaper), queue(3) intrusive links that make the process an entry on some list, or queue(3) heads that start a new list specific to this process (e.g., the list of our children). If you stare at the definition of struct proc long enough to get over how ugly the queue(3) macros are, you’ll notice something:

You cannot even look at the definition of what a process is without immediately seeing all the data structures it lives in, and what the nature of the relationships are.

For example, a process can be an orphan (it has linkage into the global list of orphans on line 47) and it can act as the adopted parent of orphans (typically only init does this), using the list head on line 48. Orphans and zombies are a rather esoteric bit of UNIX architecture, and you will probably forget them. But seeing the definition of <sys/proc.h> is enough to immediately remember it. Moreover, you can’t help but see it, every time you look at the definition of struct proc – which is often! Before you know it, you’ve learned a critical aspect of the OS design and the code which implements it!

Neatly collecting all this information in one well-defined, easy-to-remember place is a comprehension super-power. Not only that, but it is further enhanced by the style of the FreeBSD architectural documentation: there is typically an intimate relationship between the diagrams in the book, and the structure of the code.

Look again at the process diagram above. Like so many “enterprise architect” diagrams, this picture may appear to be an abstract block diagram which only hints at the relationships between processes – but it is not. The elegant simplicity of the intrusive lists means that the arrows do not represent some abstract (i.e., hard-to-understand) “relationship.” The boxes are instances of struct proc and the arrows are literally just the linkage pointers in the intrusive lists. The diagram doesn’t “suggest” how the data is organized – it is more like a concrete representation of the in-memory objects.

If you study FreeBSD, you tend to have the following experience: first you read a chapter in the book that explains a high-level concept. Despite being conceptual (there is almost no source code in the book), the relationships between concepts are usually illustrated in a diagram like the one above. Then you pick up the source code. It is usually trivial to discover how the concept is modeled in the code, because despite being written in C, UNIX is a marvel of “object oriented” design: every concept gets a language-level object (usually a struct) that explicitly models it, with the same name. It is also trivial to discover how it relates to all the other concepts: there are usually queue(3) entries to all the structures modeling the related concepts, exactly as they appear in the diagram. You are rarely at a loss to understand where something is defined. Even if all you have is grep, knowing the name of the queue(3) entry member is usually enough to find all users/modifiers of the relationship.

Why does it work?

Many of us in the C++ developer community know Sean Parent; he has given a number of well-received talks at various C++ conferences. One theme in his talks is that it is critical to be able to “locally reason about code.” The big question is: do I have to look at one place in the code to understand what’s going on, or do I have to look everywhere. The cost of just finding all the places you’re supposed to look will increase as program size increases, and the comprehension cost will increase much more dramatically. In one of his most popular talks, he emphasizes using value semantics where possible – the lack of reference semantics means no other part the program (no matter how large!) can possibly affect the code we’re looking at.

I think he’s on to something: it seems that all the comprehension superpowers I know – indentation, value semantics, intrusive lists, etc. – ultimately derive their power from how they enrich a small piece of text with a lot of information.

Early in the development of CSD, intrusive entry objects did not re-specify the type of linked list they lived in, i.e., code using CSD used to look like this:

struct ListItem {

int i;

tailq_entry e; // Note: not a template

};

Later, it was changed to its current form:

struct ListItem {

int i;

tailq_entry<ListItem> e; // Link us into a list of other ListItems

};

This is redundant, and the template makes the implementation more complex. It was changed because after a long hiatus of not reading any FreeBSD kernel code, I returned to it and discovered that it makes some small difference – in terms of “effortless comprehension” – to see the type of the list locally restated. Look again at the above code listing for the FreeBSD process structure, struct proc. All the entry macros restate that their purpose is to join a struct proc into a data structure containing other struct proc instances, e.g., LIST_ENTRY(proc) p_list for the global process list.

This is needed in queue(3) because of how the implementation works, but it is not strictly necessary in CSD. In the old code, that the e member links us into a list of other ListItem instances is implicit: we know it’s true because we’re using an intrusive list and by definition, intrusive lists link the kind of objects that contain the intrusive linkage. The old way wasn’t exactly hard to understand without this extra comprehension cue, but it lacked the clarity evident in the struct proc example. This originally went unnoticed because it doesn’t make much of a difference in simple examples, like the one above. As the structures grow larger, it becomes more difficult to keep track of things that are implicit/contextual. As CSD was used more extensively, it became clear that the original queue(3) style was better because it improved – in the words of Sean Parent – the “ability to locally reason about code.”

For what it’s worth, I don’t think Sean Parent would be that enamored of intrusive lists: they are typically reference-heavy structures that point all over the place. That said, I doubt there is much of an alternative. Look at the sheer number of different data structures that a struct proc must simultaneously live in. This number cannot be reduced; the complexity of those relationships is specified by the UNIX process model, which has served us well for decades; it’s a good design we want to keep. Our goal is to create a source code design that helps us “mentally manage” that complexity. Intrusive lists make it possible to see all these relationships together and to draw clear architecture diagrams of how they appear in code. That makes it easier for new engineers to learn that architecture and the kernel code base, ensuring that UNIX continues to march on to victory.

- 1

Chief among these anti-patterns is outsourcing the relationship management to some kind of in-memory database, i.e., model your core data structures using database primitives and hope the database’s query language will help you “slice and dice” the data. The rich object graphs formed by intrusive data structures are already “highly navigable”, and linking into a hash table or balanced tree is analogous to creating an “index” on that attribute of the data.